The Leavitt-Walker administration redefined transportation in the State of Utah from its earliest days. In January 1993, Governor Michael O. Leavitt determined that a course change was needed at the Department of Transportation and appointed W. Craig Zwick as its executive director. It was a move calculated to restore public confidence in an agency that Governor Leavitt knew would play a significant role in addressing the needs of the citizens of the state. Craig Zwick came to the agency with years of private sector construction experience having owned Zwick Construction up until a few years before his appointment. He had just completed serving as a mission president for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and came to the Utah Department of Transportation (UDOT) with fresh ideas and an enthusiasm that energized the employees and changed the very nature of the agency.

At the time of Craig Zwick’s appointment the deputy director of UDOT was Howard Richardson, a long-time employee of the agency. Within the year, Howard retired and Clint D Topham was appointed to serve in this role. It was the Zwick Topham combination that launched UDOT on its course to becoming one of the most admired and respected government agencies in the state during the Walker-Leavitt years. Craig Zwick had an amazing ability for relating to people and the employees soon came to respect him and were willing to make the changes necessary to move UDOT from a traditional governmental entity to one that could operate in new ways.

At the time of Craig Zwick’s appointment the deputy director of UDOT was Howard Richardson, a long-time employee of the agency. Within the year, Howard retired and Clint D Topham was appointed to serve in this role. It was the Zwick Topham combination that launched UDOT on its course to becoming one of the most admired and respected government agencies in the state during the Walker-Leavitt years. Craig Zwick had an amazing ability for relating to people and the employees soon came to respect him and were willing to make the changes necessary to move UDOT from a traditional governmental entity to one that could operate in new ways.

The Utah statutes provide for the establishment of a State Transportation Commission. The Commission was comprised of five individuals appointed by the Governor for terms of six years. Four served from specific districts as described in state law. The fifth, served at-large. At the time of Craig Zwick’s appointment as the Executive Director of UDOT, the commission members included the following: Sam Taylor-Chairman, Grey Larkin, Todd Weston, Wayne Winters, and Ted Lewis. Several had served for multiple terms having been reappointed by past governors.

The Utah statutes provide for the establishment of a State Transportation Commission. The Commission was comprised of five individuals appointed by the Governor for terms of six years. Four served from specific districts as described in state law. The fifth, served at-large. At the time of Craig Zwick’s appointment as the Executive Director of UDOT, the commission members included the following: Sam Taylor-Chairman, Grey Larkin, Todd Weston, Wayne Winters, and Ted Lewis. Several had served for multiple terms having been reappointed by past governors.

The long-standing nature of the Commission members’ appointments and a history of tradition resulted in concerns that the Executive Director’s duties and those described in statute by the Commission were in conflict. Not in the way they were described in the law but in the way that their roles had evolved over time. Craig Zwick realized that his ability to take UDOT in the direction that it needed to go was constrained due to this lack of clarity and correctness in how the two filled their respective roles. What ensued was a redefinition of roles that played out at the legislature, in the governor’s office and in the halls of UDOT. In the end, Sam Taylor resigned as Chairman of the Commission and Wayne Winters’ term had expired. Glen Brown from Coalville (former legislator and Speaker of the House) was named as Chairman and Hal Clyde of Springville completed the five-member commission. The department embraced many changes during the leadership provided Zwick and Topham. Processes were changed, morale improved, projects were advanced and the agency  was deeply engaged in improving transportation for the state. Simply stated, the Commission returned to its statutory role of determining the priorities for highway projects in the state and the Executive Director focused on leading the agency.

was deeply engaged in improving transportation for the state. Simply stated, the Commission returned to its statutory role of determining the priorities for highway projects in the state and the Executive Director focused on leading the agency.  In April 1995, W. Craig Zwick was named by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints as a member of their First Quorum of Seventy. He immediately assumed that role and Governor Leavitt needed to find another director for his transportation agency. In May 1995, Thomas R. Warne was named as the new Executive Director of UDOT. Clint D Topham remained as the Deputy Director and the two of them spent the next five years together advancing important transportation initiatives throughout the state. Some would suggest that Craig Zwick’s tenure at UDOT, lasting just over two years, was too short to make a difference in the state’s transportation system. In fact, several years later during the height of the I-15 Reconstruction Project, Tom Warne was the keynote speaker at a luncheon in Salt Lake City and the individual at his side on the dais noted that it was too bad that Craig Zwick didn’t rebuild I-15 while he was the director of UDOT. Tom Warne replied that Craig had everything to do with the getting the I-15 Reconstruction Project started. Tom explained that during Craig’s tenure he redefined the roles of the director and the Commission allowing him to lead the agency through the complex technical process of launching the nation’s largest transportation project ever and that Craig Zwick “healed” a wounded agency from its years of public criticism and leadership challenges. Tom further noted that Craig set the stage so that he could launch and complete the I-15 Reconstruction Project—an achievement that would not have been possible otherwise. When Tom Warne arrived the I-15 Reconstruction Project was in its final planning stages. The environmental studies were nearly complete and a basic staff for the project was in place doing basic engineering and other preparations. The existing I-15 was severely deteriorated and no question existed as to the urgency of the mission for UDOT to replace the facility sooner than later.

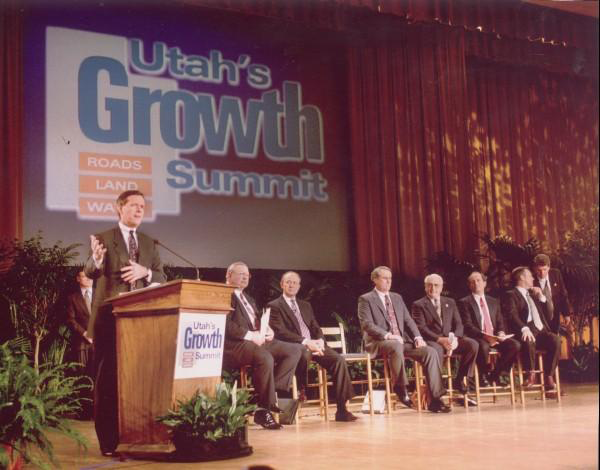

In April 1995, W. Craig Zwick was named by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints as a member of their First Quorum of Seventy. He immediately assumed that role and Governor Leavitt needed to find another director for his transportation agency. In May 1995, Thomas R. Warne was named as the new Executive Director of UDOT. Clint D Topham remained as the Deputy Director and the two of them spent the next five years together advancing important transportation initiatives throughout the state. Some would suggest that Craig Zwick’s tenure at UDOT, lasting just over two years, was too short to make a difference in the state’s transportation system. In fact, several years later during the height of the I-15 Reconstruction Project, Tom Warne was the keynote speaker at a luncheon in Salt Lake City and the individual at his side on the dais noted that it was too bad that Craig Zwick didn’t rebuild I-15 while he was the director of UDOT. Tom Warne replied that Craig had everything to do with the getting the I-15 Reconstruction Project started. Tom explained that during Craig’s tenure he redefined the roles of the director and the Commission allowing him to lead the agency through the complex technical process of launching the nation’s largest transportation project ever and that Craig Zwick “healed” a wounded agency from its years of public criticism and leadership challenges. Tom further noted that Craig set the stage so that he could launch and complete the I-15 Reconstruction Project—an achievement that would not have been possible otherwise. When Tom Warne arrived the I-15 Reconstruction Project was in its final planning stages. The environmental studies were nearly complete and a basic staff for the project was in place doing basic engineering and other preparations. The existing I-15 was severely deteriorated and no question existed as to the urgency of the mission for UDOT to replace the facility sooner than later.  During the summer of 1995 the plan for rebuilding I-15 from 600 North to 106th South was to break it up into 15 or 20 construction contracts that would be built over an eight to ten year period beginning in 1997 or 1998. The estimated cost for the whole project at this point was around $900 million. Utah had never built a project worth over $50 million so the paradigm was focused on something in that range for each one. At the time, the largest single contract in the country was the San Joaquin Toll Road in southern California which was in the $700 million dollar range. In July 1995 a change in leadership occurred on the I-15 Team with David Downs taking the reigns as their new leader. Planning and engineering continued on the I-15 Reconstruction Project through the summer of 1995 and into the fall of that year. In late October Tom Warne was invited up to the Governor’s office to meet with Mike Leavitt and his then Chief of Staff, Charlie Johnson. The purpose of the meeting was to discuss the I-15 Reconstruction Project and how it was to be built. It was a short meeting. Basically the Governor said the following: “Tom, it would be a bad thing to have I-15 under construction during the 2002 Winter Olympic Games. I need you to find a way to finish it before the Olympics.” That was it. Tom Warne left and headed straight to a meeting of his I-15 Team that was going at a location in Lake City. Interrupting that meeting, Tom explained to the team members the charge he had, only moments before, gotten from the Governor—finish I-15 by the Fall of 2001. The group was stunned to say the least. A few questions were asked and Tom left. One engineer was so shocked that he followed Tom out into the hall and wondered if Tom really knew what he had just said. He was assured and the I-15 Team immediately embarked on the process to figure out how to meet the Governor’s challenge. In less than an hour the contract duration for the I-15 Reconstruction Project went from eight to ten years to four and a half years. November passed and the team worked on solutions. Eventually they came to Tom Warne with the proposal to build the I-15 Reconstruction Project using a contract delivery method called design-build. No one on the team had any experience with this process but many private sector projects around the country had used it and several toll road projects had utilized it as well. Tom’s total experience with design-build was a $25 million bridge in Yuma, Arizona a few years earlier while serving as the Deputy Director of the Arizona Department of Transportation. In the next two months the department sought and received approval from the Governor, key legislative leaders, and the State Transportation Commission to pursue design-build. It is impossible to tell the UDOT story of the Leavitt-Walker years without relating everything to I-15 since it was the catalyst for so many of the changes that occurred in transportation during that period of time. That said, other significant and related activities were going on that were critical to the changing transportation systems in the state. One of these was the Growth Summit that Governor Leavitt led during the late summer and fall of 1995. The Growth Summit was launched in response to the need for Utahans to address some of the impacts of the state’s phenomenal growth. Three topics were the focus of the Growth Summit-Transportation, Water and Open Space. Public meetings were held, thoughtful discussion occurred and the state was noticeably engaged in an important public policy exchange that would have long-term impacts on its future. The Growth Summit was important to the overall I-15 effort because it set the stage for substantive discussions about transportation and a sustainable revenue stream to fund it and other projects around the state. While no new funding became available in the 1996 legislative session a key change in state law paved the way for UDOT to pursue the reconstruction of I-15 as a single project now valued at $1 billion. The need for rebuilding I-15 was more than apparent as its deteriorated condition was easily viewed. Sept. 15 – Governor’s Growth Summit, Michael Leavitt, Tom Warne (UDOT Director) 28277847

During the summer of 1995 the plan for rebuilding I-15 from 600 North to 106th South was to break it up into 15 or 20 construction contracts that would be built over an eight to ten year period beginning in 1997 or 1998. The estimated cost for the whole project at this point was around $900 million. Utah had never built a project worth over $50 million so the paradigm was focused on something in that range for each one. At the time, the largest single contract in the country was the San Joaquin Toll Road in southern California which was in the $700 million dollar range. In July 1995 a change in leadership occurred on the I-15 Team with David Downs taking the reigns as their new leader. Planning and engineering continued on the I-15 Reconstruction Project through the summer of 1995 and into the fall of that year. In late October Tom Warne was invited up to the Governor’s office to meet with Mike Leavitt and his then Chief of Staff, Charlie Johnson. The purpose of the meeting was to discuss the I-15 Reconstruction Project and how it was to be built. It was a short meeting. Basically the Governor said the following: “Tom, it would be a bad thing to have I-15 under construction during the 2002 Winter Olympic Games. I need you to find a way to finish it before the Olympics.” That was it. Tom Warne left and headed straight to a meeting of his I-15 Team that was going at a location in Lake City. Interrupting that meeting, Tom explained to the team members the charge he had, only moments before, gotten from the Governor—finish I-15 by the Fall of 2001. The group was stunned to say the least. A few questions were asked and Tom left. One engineer was so shocked that he followed Tom out into the hall and wondered if Tom really knew what he had just said. He was assured and the I-15 Team immediately embarked on the process to figure out how to meet the Governor’s challenge. In less than an hour the contract duration for the I-15 Reconstruction Project went from eight to ten years to four and a half years. November passed and the team worked on solutions. Eventually they came to Tom Warne with the proposal to build the I-15 Reconstruction Project using a contract delivery method called design-build. No one on the team had any experience with this process but many private sector projects around the country had used it and several toll road projects had utilized it as well. Tom’s total experience with design-build was a $25 million bridge in Yuma, Arizona a few years earlier while serving as the Deputy Director of the Arizona Department of Transportation. In the next two months the department sought and received approval from the Governor, key legislative leaders, and the State Transportation Commission to pursue design-build. It is impossible to tell the UDOT story of the Leavitt-Walker years without relating everything to I-15 since it was the catalyst for so many of the changes that occurred in transportation during that period of time. That said, other significant and related activities were going on that were critical to the changing transportation systems in the state. One of these was the Growth Summit that Governor Leavitt led during the late summer and fall of 1995. The Growth Summit was launched in response to the need for Utahans to address some of the impacts of the state’s phenomenal growth. Three topics were the focus of the Growth Summit-Transportation, Water and Open Space. Public meetings were held, thoughtful discussion occurred and the state was noticeably engaged in an important public policy exchange that would have long-term impacts on its future. The Growth Summit was important to the overall I-15 effort because it set the stage for substantive discussions about transportation and a sustainable revenue stream to fund it and other projects around the state. While no new funding became available in the 1996 legislative session a key change in state law paved the way for UDOT to pursue the reconstruction of I-15 as a single project now valued at $1 billion. The need for rebuilding I-15 was more than apparent as its deteriorated condition was easily viewed. Sept. 15 – Governor’s Growth Summit, Michael Leavitt, Tom Warne (UDOT Director) 28277847  Sept. 15 – Governor’s Growth Summit, Michael Leavitt, Speaker Mel Brown, Sen Pres Lane Beattie, ?, ?, Rep. Frank Pignanelli, Sen. Scott Howell 810406

Sept. 15 – Governor’s Growth Summit, Michael Leavitt, Speaker Mel Brown, Sen Pres Lane Beattie, ?, ?, Rep. Frank Pignanelli, Sen. Scott Howell 810406  State statute was very specific about how UDOT could procure contractors for its highway contracts. Typically, the state used a process called design-bid-build where UDOT would design the project, advertise it for bids and then select the lowest bidder to build the work. It was a tool that UDOT had used for years and was very familiar with. The change that UDOT needed to meet the four and a half year challenge was the authority to procure the contractor using the design-build approach. This required legislative approval and was an important achievement for UDOT and the state in the 1996 legislative session. Some controversy accompanied the process but winning the day set the stage for what would come in the year that followed. Ironically, several years later when the Utah Transit Authority (UTA) was seeking authority to use design-build on their light rail projects a hearing was being held in the Senate Transportation Committee that Tom Warne attended. John Inglish, the UTA General Manager, was presenting to the committee that UTA sought authority to do design-build for its future light rail projects. At one point, the late Senator Eddie Mayne (D) West Valley City, interrupted John Inglish’s testimony. Calling to Tom Warne in the audience he said, “Tom, isn’t this the way we’re re-building I-15?” To which Tom responded, “Yes.” Senator Mayne then made the motion for the committee to approve UTA’s request, another member seconded his motion, a vote was immediately taken and John Inglish left having given very little of his prepared testimony. Such was the support exhibited by legislators for UDOT and how successful the design-build approach was seen by them. In the spring of 1996 UDOT conducted a poll through a local firm, Dan Jones and Associates. In that poll the citizens were asked how about the relationship between speed in construction and inconvenience. In the end the public said, “They would rather endure more pain and inconvenience for a shorter period of time than have the I-15 Reconstruction Project last longer.” Armed with this convincing sentiment UDOT felt confident in moving ahead with the accelerated design-build schedule on I-15. Another factor considered important in the acceleration discussion was how the community would benefit from a project being completed sooner than later. The late Thayne Robison, a renowned Utah economist concluded that the savings in construction costs due to inflation and other factors would be on the order of $500 million and that the economic benefits to the community would equal that number as well. The year 1996 was spent preparing a request for proposals for the I-15 Reconstruction Project. With statutory authority to use this process UDOT then turned its attention to moving the project ahead so that by the next legislative session funds could be raised to actually pay for the new work. Apr 20 Jackie Leavitt, Michael Leavitt, UDOT Director Tom Warne, Lynne Ward taking a tour of I-15 under construction at about 90th South 13598682

State statute was very specific about how UDOT could procure contractors for its highway contracts. Typically, the state used a process called design-bid-build where UDOT would design the project, advertise it for bids and then select the lowest bidder to build the work. It was a tool that UDOT had used for years and was very familiar with. The change that UDOT needed to meet the four and a half year challenge was the authority to procure the contractor using the design-build approach. This required legislative approval and was an important achievement for UDOT and the state in the 1996 legislative session. Some controversy accompanied the process but winning the day set the stage for what would come in the year that followed. Ironically, several years later when the Utah Transit Authority (UTA) was seeking authority to use design-build on their light rail projects a hearing was being held in the Senate Transportation Committee that Tom Warne attended. John Inglish, the UTA General Manager, was presenting to the committee that UTA sought authority to do design-build for its future light rail projects. At one point, the late Senator Eddie Mayne (D) West Valley City, interrupted John Inglish’s testimony. Calling to Tom Warne in the audience he said, “Tom, isn’t this the way we’re re-building I-15?” To which Tom responded, “Yes.” Senator Mayne then made the motion for the committee to approve UTA’s request, another member seconded his motion, a vote was immediately taken and John Inglish left having given very little of his prepared testimony. Such was the support exhibited by legislators for UDOT and how successful the design-build approach was seen by them. In the spring of 1996 UDOT conducted a poll through a local firm, Dan Jones and Associates. In that poll the citizens were asked how about the relationship between speed in construction and inconvenience. In the end the public said, “They would rather endure more pain and inconvenience for a shorter period of time than have the I-15 Reconstruction Project last longer.” Armed with this convincing sentiment UDOT felt confident in moving ahead with the accelerated design-build schedule on I-15. Another factor considered important in the acceleration discussion was how the community would benefit from a project being completed sooner than later. The late Thayne Robison, a renowned Utah economist concluded that the savings in construction costs due to inflation and other factors would be on the order of $500 million and that the economic benefits to the community would equal that number as well. The year 1996 was spent preparing a request for proposals for the I-15 Reconstruction Project. With statutory authority to use this process UDOT then turned its attention to moving the project ahead so that by the next legislative session funds could be raised to actually pay for the new work. Apr 20 Jackie Leavitt, Michael Leavitt, UDOT Director Tom Warne, Lynne Ward taking a tour of I-15 under construction at about 90th South 13598682  The process of preparing the solicitation documents, working with the engineering and construction industries and all of the related activities took a huge effort. Besides David Downs the I-15 Team included other key individuals including John Higgins, John Leonard, and Dave Nazare. In addition, the agency utilized an outside engineering firm by the name of Parsons Brinkerhoff (PB) to add staff and expertise to the team. Key participants from PB included Mike Robertson and Pat Drennon. After about a year of construction, UDOT’s leadership on the I-15 Team shifted to John Bourne as the project manager with Dallis Hawks serving as his deputy. It was under their leadership that the bulk of the project was built. As large as the project was, UDOT chose to divide it into three segments to match the manner in which Wasatch Constructors was organized. The three segment managers for UDOT were Joe Kemmerer, Richard Miller and Lonny Marchant. A major activity during 1996 was determining how the project was going to be funded. Interest was high in how much the final project was going to cost. Utah had never built a $1 billion project before. Nor had any other state DOT in the country accomplished such a task. The $900 million estimate was not changed through much of 1996 while the scope of the project was being refined. One spring day in 1996 there was an urgent request from the Governor’s office for an updated estimate. Most of the I-15 staff was at UDOT’s annual Engineer’s Conference held at Snowbird, Utah. The call came to Tom Warne and the request for an updated I-15 cost estimate was needed in an hour. Snowbird was very busy that afternoon with most of its rooms and meeting areas being occupied. Tom gathered about half a dozen members of the I-15 Team including David Downs and UDOT’s Deputy Director, Clint Topham in the vacant seating area of the main lounge of the resort as it was the only available space. In less than 30 minutes this group adjusted the estimate for the I-15 Reconstruction Project upward to $1 billion. Ironically, the calculations were all done on a small cocktail napkin on a table in the center of the group. The new number was sent forward with no one outside of this little group knowing its genesis. In the fall of 1996 it became clear that a funding source for the I-15 Reconstruction Project would require substantial support in the legislature. That said, there were many legislators whose constituents would not directly benefit from the expenditures in Salt Lake County. The need to garner widespread support necessitated a statewide review of transportation needs and a recognition that some of these other needs would have to be addressed at the same time the I-15 problems were being solved. Governor Leavitt sent Chairman Glen Brown, Tom Warne and Clint Topham to every legislator who was willing to meet them to discuss transportation needs in their districts. They traveled the state and held meetings with almost every member of the Utah State House and many of the members of the Senate. From those meetings came a list of about 200 projects that represented the highest priorities for each of the elected officials involved. It was from this list that the original Centennial Highway Fund (CHF) group of projects emerged. The I-15 procurement was a one-of-a-kind effort. Certainly there had been smaller design-build projects advanced in the country—but nothing as large or complex as Utah’s first design-build effort. The I-15 Team met their goal of having the request for proposals (RFP) out to the construction community by October 1, 1996. Teams of contractors and engineers had formed and it appeared there would be at least three and maybe four proposals submitted to the department. Those interested in being considered would have to send in their proposal by early January 1997. At that time it was hoped that UDOT would then have a number against which the legislature and the governor’s office could craft a funding package to support the project. Throughout the fall of 1996 three teams worked on their proposals for UDOT. A word about political support for UDOT and the I-15 Reconstruction Project is appropriate. Words cannot describe now supportive Governor Leavitt and Lt. Governor Walker were of UDOT, Tom Warne and Clint Topham and the I-15 Reconstruction Project. At every turn they were willing to extend themselves, use political capital to support the agency and do all in their power to ensure the success of the project. In many forums the Governor would send the clear message to whoever needed to hear it that—“you mess with Tom or UDOT and you’re messing with me.” The support from legislative leadership was also extremely high. At that time Senator Lane Beattie was the President of the Senate and Speaker Melvin Brown (R) Murray, led the State House. Both were staunch supporters of the I-15 Reconstruction Project and extended no small amount of their personal capital to ensure that the project got it funding and that there were no legislative barriers placed in the path of its completion. In a report at the end of the I-15 Reconstruction Project Tom Warne noted that one of the major lessons learned in completing such an effort was that there was really no limit to what an agency like UDOT could accomplish with such strong support from the Governor’s office and legislative leadership. The buzz in the transportation industry across the country about Utah and the I-15 Reconstruction Project was amazing.

The process of preparing the solicitation documents, working with the engineering and construction industries and all of the related activities took a huge effort. Besides David Downs the I-15 Team included other key individuals including John Higgins, John Leonard, and Dave Nazare. In addition, the agency utilized an outside engineering firm by the name of Parsons Brinkerhoff (PB) to add staff and expertise to the team. Key participants from PB included Mike Robertson and Pat Drennon. After about a year of construction, UDOT’s leadership on the I-15 Team shifted to John Bourne as the project manager with Dallis Hawks serving as his deputy. It was under their leadership that the bulk of the project was built. As large as the project was, UDOT chose to divide it into three segments to match the manner in which Wasatch Constructors was organized. The three segment managers for UDOT were Joe Kemmerer, Richard Miller and Lonny Marchant. A major activity during 1996 was determining how the project was going to be funded. Interest was high in how much the final project was going to cost. Utah had never built a $1 billion project before. Nor had any other state DOT in the country accomplished such a task. The $900 million estimate was not changed through much of 1996 while the scope of the project was being refined. One spring day in 1996 there was an urgent request from the Governor’s office for an updated estimate. Most of the I-15 staff was at UDOT’s annual Engineer’s Conference held at Snowbird, Utah. The call came to Tom Warne and the request for an updated I-15 cost estimate was needed in an hour. Snowbird was very busy that afternoon with most of its rooms and meeting areas being occupied. Tom gathered about half a dozen members of the I-15 Team including David Downs and UDOT’s Deputy Director, Clint Topham in the vacant seating area of the main lounge of the resort as it was the only available space. In less than 30 minutes this group adjusted the estimate for the I-15 Reconstruction Project upward to $1 billion. Ironically, the calculations were all done on a small cocktail napkin on a table in the center of the group. The new number was sent forward with no one outside of this little group knowing its genesis. In the fall of 1996 it became clear that a funding source for the I-15 Reconstruction Project would require substantial support in the legislature. That said, there were many legislators whose constituents would not directly benefit from the expenditures in Salt Lake County. The need to garner widespread support necessitated a statewide review of transportation needs and a recognition that some of these other needs would have to be addressed at the same time the I-15 problems were being solved. Governor Leavitt sent Chairman Glen Brown, Tom Warne and Clint Topham to every legislator who was willing to meet them to discuss transportation needs in their districts. They traveled the state and held meetings with almost every member of the Utah State House and many of the members of the Senate. From those meetings came a list of about 200 projects that represented the highest priorities for each of the elected officials involved. It was from this list that the original Centennial Highway Fund (CHF) group of projects emerged. The I-15 procurement was a one-of-a-kind effort. Certainly there had been smaller design-build projects advanced in the country—but nothing as large or complex as Utah’s first design-build effort. The I-15 Team met their goal of having the request for proposals (RFP) out to the construction community by October 1, 1996. Teams of contractors and engineers had formed and it appeared there would be at least three and maybe four proposals submitted to the department. Those interested in being considered would have to send in their proposal by early January 1997. At that time it was hoped that UDOT would then have a number against which the legislature and the governor’s office could craft a funding package to support the project. Throughout the fall of 1996 three teams worked on their proposals for UDOT. A word about political support for UDOT and the I-15 Reconstruction Project is appropriate. Words cannot describe now supportive Governor Leavitt and Lt. Governor Walker were of UDOT, Tom Warne and Clint Topham and the I-15 Reconstruction Project. At every turn they were willing to extend themselves, use political capital to support the agency and do all in their power to ensure the success of the project. In many forums the Governor would send the clear message to whoever needed to hear it that—“you mess with Tom or UDOT and you’re messing with me.” The support from legislative leadership was also extremely high. At that time Senator Lane Beattie was the President of the Senate and Speaker Melvin Brown (R) Murray, led the State House. Both were staunch supporters of the I-15 Reconstruction Project and extended no small amount of their personal capital to ensure that the project got it funding and that there were no legislative barriers placed in the path of its completion. In a report at the end of the I-15 Reconstruction Project Tom Warne noted that one of the major lessons learned in completing such an effort was that there was really no limit to what an agency like UDOT could accomplish with such strong support from the Governor’s office and legislative leadership. The buzz in the transportation industry across the country about Utah and the I-15 Reconstruction Project was amazing.

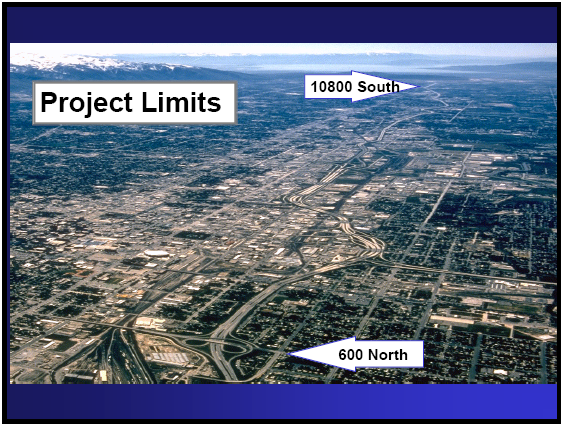

Many people couldn’t believe a public agency would take such a risk. Others applauded the effort and wished their states would do something similar. One major journal of the engineering community that paid particular attention to I-15 was Engineering News Record (ENR). ENR did many stories about the project over the course of a five-year period giving detailed information to its widely dispersed subscriber base. Tom Warne came to UDOT after serving as the Deputy Director of the Arizona Department of Transportation (ADOT) for several years under its Director, Larry S. Bonine. At one point in 1996 Larry called Tom up and said the following: “You’ve got a lot of guts doing this I-15 Reconstruction Project as one big billion dollar contract. If you pull it off, you guys will be on the cover of ENR. Of course, if you don’t pull it off and fail you’ll still be on the cover of ENR.” Such was the pressure on Tom Warne, UDOT and the I-15 Team. The day proposals were due at UDOT their delivery was one of the top news stories in the state. Video clips of boxes being brought into the I-15 office were shown on television that night with excited commentary from the anchors. To the public, this was the first major step in getting this project moving ahead. The review process for the project took two months. It involved over 60 individuals representing all the engineering disciplines that would be involved in the project including structures, drainage, lighting, pavement, etc. Security was tight to ensure the private sector firms who proposed that their ideas and prices would be kept confidential throughout the process. Once in UDOT’s possession the technical proposals comprised of many boxes of information were stored in a secure area of the I-15 Team’s offices. The pricing information was taken off-site and stored in a Safe Deposit Box at a local branch of Zions Bank. UDOT was determined that the content of these proposals was not going to be compromised. While the contractor’s were putting their proposals and prices together UDOT hired a contractor from the southeast to do an independent estimate for the project cost. That estimate came back to UDOT in early December of 1996 and indicated that the price was going to be in the neighborhood of $1.3 billion. UDOT had not updated its estimate since June of 2006 due to the speed of the procurement process and the many changes that were occurring right up until the solicitation was released. Ultimately, the proposals came in at the same level as UDOT’s independent contractor’s estimate. The 1997 legislative session was intense in many ways—especially around the subject of transportation. Fear among other agencies and constituent groups was high as the talk about how to raise billions of dollars for transportation was evident everywhere. At one point education supporters felt like it was going to fall victim to the transportation tide. In an effort to get their message out to the Representatives and Senators school children were brought to the capitol rotunda area to walk around in t-shirts that had tire tracks across their back and the statement, “Don’t pave over me.” The earlier effort launched by Governor Leavitt to determine which projects the legislators thought were most important began to pay off as the session wore on. The list of 200 projects eventually became the centerpiece of the funding proposals being advanced. As the session drew to a close the list of projects that would be included in the CHF took shape. One afternoon, just days before adjournment, President Lane Beattie summoned Tom Warne and Clint Topham to the Senate offices and asked them to prepare a cost estimate for 22 projects and have it ready for their leadership meeting the next morning. Clint took the list home that night and early the next morning came in with the cost estimates for all of the projects. In many cases there was not a detailed scope or description of the work but Clint, using his long years of transportation planning experience, came up with the numbers for each one. In retrospect, Clint Topham’s valuation of the original list of CHF projects was very accurate and became the template against which all other planning and funding decisions were made for some time to come. Many plans were put forward for funding what would become the CHF list of projects. Ultimately, the plan included a five-cent gas tax increase, commitment of new federal dollars, and a modest contribution from the general fund. In all, the CHF plan totaled $2.83 billion with about half of that dedicated to the I-15 Reconstruction Project. Exhibit A includes the list of projects and funding plan that emerged as the Centennial Highway Fund. The only additional project shown in this exhibit that wasn’t an original project in 1997 was the 114th South Interchange in Sandy which was added the next year. With funding in place the I-15 Team’s evaluation of the three proposals that it received proceeded to its close. On March 25, 1997 the announcement of the successful team would be made. On that day, the auditorium of the State Office Building was packed to capacity as engineers, contractors, elected officials and others gathered to hear the announcement of the winning team. Live television coverage brought the event to interested Utahans as Tom Warne announced that Wasatch Constructors was the successful proposer. It was an historic day for Utah and the transportation industry to be sure. The picture below shows the project limits On from 600 North in Salt Lake City to 106th South in Sandy.  The bid price by Wasatch Constructors was $1.325 billion and they committed to complete the project in 4.5 years, finishing by October 15, 2001 but opening the completed freeway no later than July 15, 2001. The Wasatch Constructors team included contractors Kiewit, Granit Construction and the Washington Group as well as Parsons Transportation Group as their principle engineer. April 15, 1997, ground was broken and work proceeded in earnest. A few facts serve to communicate the magnitude of this project. They include: 144 new bridges

The bid price by Wasatch Constructors was $1.325 billion and they committed to complete the project in 4.5 years, finishing by October 15, 2001 but opening the completed freeway no later than July 15, 2001. The Wasatch Constructors team included contractors Kiewit, Granit Construction and the Washington Group as well as Parsons Transportation Group as their principle engineer. April 15, 1997, ground was broken and work proceeded in earnest. A few facts serve to communicate the magnitude of this project. They include: 144 new bridges

- 17 miles of new interstate freeway

- 10-12 lanes wide

- 3.4 million square yards of concrete

- 3 major freeway to freeway interchanges (I-15/I-215, I-15/I-80 at 2100 South, and I-15/I-80 at 200 North)

Work on the I-15 Reconstruction Project occurred throughout the 17 mile corridor from almost day one. The first bridge to be removed and reconstructed was the structure at 600 North in Salt Lake City. The picture at the left of this interchange shows the Single Point Urban Interchange configuration used for many of the traffic interchanges construction on the I-15 Reconstruction Project. This new design allowed for up to 30% more left turning capacity at these interchanges—dramatically improving their functionality on the corridor.  The large freeway to freeway interchanges soon took shape and the public saw progress on a daily basis. The design-build process allowed Wasatch Constructors to begin construction almost immediately and build the project in parallel with the engineering design efforts. The next series of pictures reflect some of the construction activities that occurred on the project. Concrete paving was chosen by UDOT for the main freeway lanes because of its durability and excellent maintenance record. Wasatch Constructors manufactured their own concrete and delivered it to their paving machines with great efficiency. When completed, the concrete pavement on I-15 was some of the smoothest ever constructed in the country.

The large freeway to freeway interchanges soon took shape and the public saw progress on a daily basis. The design-build process allowed Wasatch Constructors to begin construction almost immediately and build the project in parallel with the engineering design efforts. The next series of pictures reflect some of the construction activities that occurred on the project. Concrete paving was chosen by UDOT for the main freeway lanes because of its durability and excellent maintenance record. Wasatch Constructors manufactured their own concrete and delivered it to their paving machines with great efficiency. When completed, the concrete pavement on I-15 was some of the smoothest ever constructed in the country.  There were many innovations that Wasatch Constructors brought to the I-15 Reconstruction Project. Each played a role in advancing the schedule and giving the state a higher quality product that would extend the life of the facility. The next two pictures are illustrative of methods introduced by Wasatch through their design-build efforts. The first shows concrete deck panels that were placed on

There were many innovations that Wasatch Constructors brought to the I-15 Reconstruction Project. Each played a role in advancing the schedule and giving the state a higher quality product that would extend the life of the facility. The next two pictures are illustrative of methods introduced by Wasatch through their design-build efforts. The first shows concrete deck panels that were placed on  the girders and then the actual deck or riding surface was then poured on top of these panels. The panels then became part of the final structure. This allowed the contractor to eliminate the need for forming the bottom of the bridge decks before pouring the concrete for that part of the bridge. The second picture shows what is called “light weight fill.” In many locations on the project the engineers had two choices: relocate old utilities such as water lines, sewer lines or storm drains or do something that would prevent

the girders and then the actual deck or riding surface was then poured on top of these panels. The panels then became part of the final structure. This allowed the contractor to eliminate the need for forming the bottom of the bridge decks before pouring the concrete for that part of the bridge. The second picture shows what is called “light weight fill.” In many locations on the project the engineers had two choices: relocate old utilities such as water lines, sewer lines or storm drains or do something that would prevent  these utilities from being damaged by the construction. By using ‘light weight fill” the contractor was able to build the roadway areas of the freeway without relocating the utilities thus saving time and money. The “fill” was really just Styrofoam blocks stacked on top of each other in place of the dirt that would normally have formed the fill under the roadway. The weight of the Styrofoam was much less than dirt and the utilities were preserved. This technique was used along I-80 near State Street and on I-15 at about 800 South. Because of the significant cash flow demands of a project the size of I-15 significant measures were required to ensure prompt payments were made to the contractor but that the state’s financial resources were properly managed. In order to control the cash outlays to the contractor a maximum payment curve was established that limited how fast the payments would be disbursed. The figure below shows both the maximum payment curve and the minimum payment curve for the I-15 Reconstruction Project. Also reflected is the contractors’ progress in terms of earnings. It should be noted that the contractor’s payments tracked very close to the maximum payment curve throughout the project. At one point the contractor was earning about $40 million a month.

these utilities from being damaged by the construction. By using ‘light weight fill” the contractor was able to build the roadway areas of the freeway without relocating the utilities thus saving time and money. The “fill” was really just Styrofoam blocks stacked on top of each other in place of the dirt that would normally have formed the fill under the roadway. The weight of the Styrofoam was much less than dirt and the utilities were preserved. This technique was used along I-80 near State Street and on I-15 at about 800 South. Because of the significant cash flow demands of a project the size of I-15 significant measures were required to ensure prompt payments were made to the contractor but that the state’s financial resources were properly managed. In order to control the cash outlays to the contractor a maximum payment curve was established that limited how fast the payments would be disbursed. The figure below shows both the maximum payment curve and the minimum payment curve for the I-15 Reconstruction Project. Also reflected is the contractors’ progress in terms of earnings. It should be noted that the contractor’s payments tracked very close to the maximum payment curve throughout the project. At one point the contractor was earning about $40 million a month.  Public information was a critical effort on the I-15 Reconstruction Project. The demand for information was nearly overwhelming at times with all forms of media giving the project lots of attention. In addition, the constantly changing nature of the closures, restrictions and other traffic issues created an environment where the public wanted information on a regular basis. In order to address this need UDOT procured the services of a local firm by the name of Wilkinson Ferrari. Led by Brian Wilkinson and Lindsey Ferrari, the I-15 public information effort became a model that has been emulated across the country. UDOT spent about .3% of the construction budget on public relations including the services of Wilkinson Ferrari, media buys, promotional materials and other communication related efforts. One thing UDOT identified early on was that there were many stakeholder groups who had unique needs on the I-15 Reconstruction Project. They included public safety, the motor carrier industry, commuters, public education and more. In all, twelve specific groups were identified and unique messaging prepared to address their needs throughout the project.

Public information was a critical effort on the I-15 Reconstruction Project. The demand for information was nearly overwhelming at times with all forms of media giving the project lots of attention. In addition, the constantly changing nature of the closures, restrictions and other traffic issues created an environment where the public wanted information on a regular basis. In order to address this need UDOT procured the services of a local firm by the name of Wilkinson Ferrari. Led by Brian Wilkinson and Lindsey Ferrari, the I-15 public information effort became a model that has been emulated across the country. UDOT spent about .3% of the construction budget on public relations including the services of Wilkinson Ferrari, media buys, promotional materials and other communication related efforts. One thing UDOT identified early on was that there were many stakeholder groups who had unique needs on the I-15 Reconstruction Project. They included public safety, the motor carrier industry, commuters, public education and more. In all, twelve specific groups were identified and unique messaging prepared to address their needs throughout the project.  The results speak for themselves. The I-15 Reconstruction Project was completed three months ahead of schedule with all lanes opened five months ahead of schedule. There were no claims or litigation that resulted between UDOT and Wasatch Constructors. And, the project was completed $32 million below budget. Perhaps the most telling of all measures was a survey done by the Deseret News on May 5, 2001 where they reported that “86% say they’d do it the same way again, if needed.” No greater endorsement of a process can be made than to have the public acclaim that it should be used again.

The results speak for themselves. The I-15 Reconstruction Project was completed three months ahead of schedule with all lanes opened five months ahead of schedule. There were no claims or litigation that resulted between UDOT and Wasatch Constructors. And, the project was completed $32 million below budget. Perhaps the most telling of all measures was a survey done by the Deseret News on May 5, 2001 where they reported that “86% say they’d do it the same way again, if needed.” No greater endorsement of a process can be made than to have the public acclaim that it should be used again.

2001 – Spaghetti Bowl reflected in detention basin, I-15 11871402

The years that followed the I-15 Reconstruction Project found UDOT going through further changes. Tom Warne left as the agency’s Executive Director in June of 2001 and was replaced by John Njord who had served as the Deputy Director since January 2000 when Clint Topham retired. Filling the Deputy Director role at that time was Carlos Braceras. Under their leadership the agency moved forward for many years—long after the Leavitt-Walker administration was over.  Overshadowed by the I-15 Reconstruction Project but no less important was the efforts undertaken by UDOT to support the 2002 Winter Olympic Games. This history of UDOT during the Leavitt-Walker administration would be incomplete without some mention of this great effort. In 1995 Salt Lake City was designated as the host city for the 2002 games. From that time forward the city, state and many others worked tirelessly to make sure that the games would be successful. John Njord was designated as the UDOT liaison to the Salt Lake Organizing Committee (SLOC) on transportation issues and filled that role as an extra assignment from his normal duties in working with local communities on their projects. In the summer of 1998, after a particularly difficult meeting between SLOC and the International Olympic Committee (IOC) a call was made from SCOC to Tom Warne asking for full-time assistance on transportation matters. From that point on John Njord became a full-time resource to SLOC until his appointment as the UDOT Deputy Director. During their tenure leading the department of transportation in the last years of the Leavitt-Walker administration John Njord and Carlos Braceras continued the legacy of leadership started by Craig Zwick and Clint Topham and continued by Tom Warne. All served on in national leadership positions in the transportation industry and the Utah Department of Transportation gained the reputation as being one of the finest agencies in the country.

Overshadowed by the I-15 Reconstruction Project but no less important was the efforts undertaken by UDOT to support the 2002 Winter Olympic Games. This history of UDOT during the Leavitt-Walker administration would be incomplete without some mention of this great effort. In 1995 Salt Lake City was designated as the host city for the 2002 games. From that time forward the city, state and many others worked tirelessly to make sure that the games would be successful. John Njord was designated as the UDOT liaison to the Salt Lake Organizing Committee (SLOC) on transportation issues and filled that role as an extra assignment from his normal duties in working with local communities on their projects. In the summer of 1998, after a particularly difficult meeting between SLOC and the International Olympic Committee (IOC) a call was made from SCOC to Tom Warne asking for full-time assistance on transportation matters. From that point on John Njord became a full-time resource to SLOC until his appointment as the UDOT Deputy Director. During their tenure leading the department of transportation in the last years of the Leavitt-Walker administration John Njord and Carlos Braceras continued the legacy of leadership started by Craig Zwick and Clint Topham and continued by Tom Warne. All served on in national leadership positions in the transportation industry and the Utah Department of Transportation gained the reputation as being one of the finest agencies in the country.